What happens in the hoof when it gets laminitis?

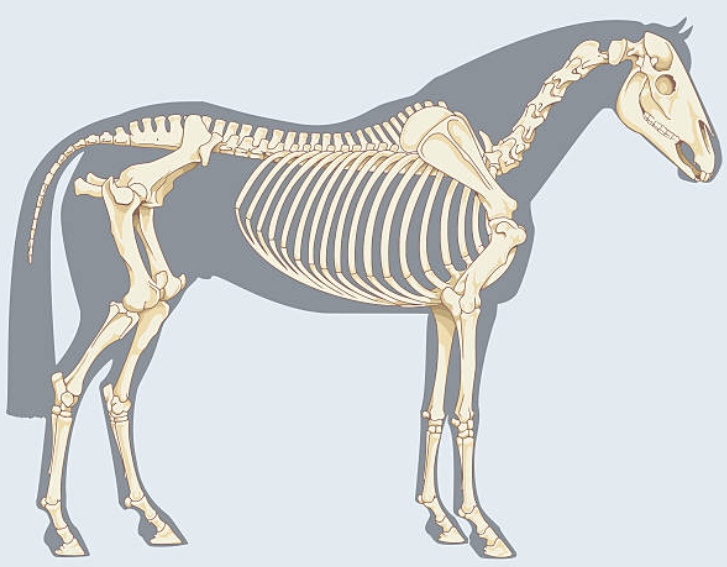

First, we must understand how the hoof is “put together” and what is attached to what. The horse’s weight is borne by the skeleton, and all the forces created by what we call weight point toward the center of the planet (i.e., straight down). The bones in the skeleton thus push directly downward against each other, causing all the weight to ultimately end up in the coffin bone.

This means that the force created by the horse’s weight causes the coffin bone to press the corium directly down toward the sole, making the hoof sink into the ground until the ground pressure equals the pressure from the horse’s weight, and the hoof stops sinking.

The picture shows a “normal” (not natural) hoof that is far too big for the coffin bone.

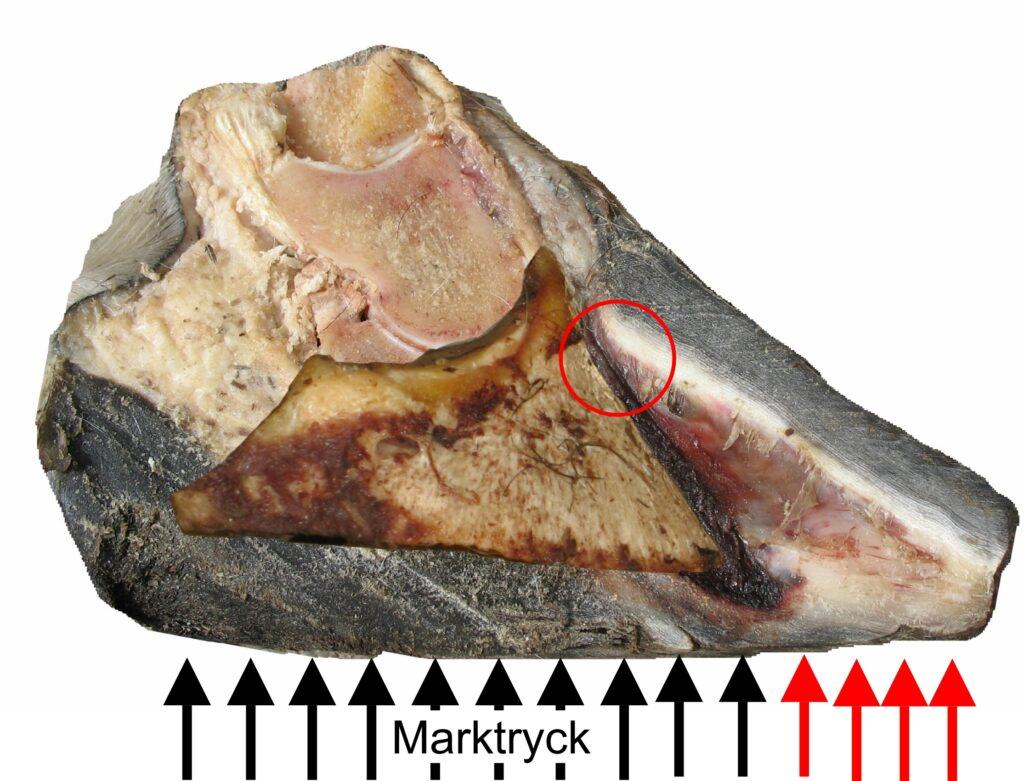

When the hoof sinks into the ground, the pressure is distributed across the entire underside of the hoof, which reduces the load per unit area. Note that the pressure from the coffin bone goes straight down, and if the hoof is larger than the coffin bone, the oversized part of the hoof will be pushed upward by the ground pressure (Red arrows), while the part directly under the coffin bone will be in balance when it comes to forces since the coffin bone will press down with the force create by the horse’s weight and ground pressure (black arrows) will be pushing up with the same force. This means that the outer part of the sole and the white line will be subjected to tensile forces upwards from ground pressure bending and stretching the sole since there is no weight pressing down.

The same applies if the hoof is shod and the hoof wall extends below the sole level, thus bearing weight. When the hoof wall is pushed upward relative to the coffin bone and the part of the sole beneath the coffin bone, unnatural forces will cause stretching of the hoof wall’s attachment (laminea) to the hoof capsule. A healthy hoof can withstand quite a lot of such forces compared to a hoof that has been affected by laminitis.

The picture above shows a hoof wall with laminea that has been torn away from the coffin bone.

In a laminitic hoof, the hoof wall will therefore be pushed upward relative to all other parts of the hoof/horse if it is forced to bear weight (be exposed to ground pressure). This can be misunderstood as the coffin bone was sinking when it is the hoof wall that i compared to everything else. Lowering of the coffin bone should therefor be called be called something like “hoof wall elevation” to make the rehabilitation more logical. As long as the condition is called distal descent or lowering of the coffin bone, rehabilitation will focus on trying to push the coffin bone back up, but since the coffin bone is in direct contact with the short pastern bone and the rest of the skeleton, there is no space into which the coffin bone can be pushed up.

When it comes to the condition of “coffin bone rotation,” the same principle applies: the horse’s entire weight, through the skeleton, presses the coffin bone straight down toward the corium, then to the sole, and then the ground. There is neither a void in the hoof for the coffin bone to rotate into, nor is there a force pushing the coffin bone’s front end downward—the short pastern bone applies pressure on the coffin bone’s rear, making such rotation physically impossible.

The blue arrow represents the horse’s weight,

and the red area shows where the coffin bone is connected to the corium.

If the coffin bone did “hang” from the red line,

would not the back part of the bone then be more prone to rotating down?

What way would the weight go in a hoof where the hoof wall, due to metal shoes or protruding hoof walls, has been made weight-bearing?

As stated before, the horse’s weight should be transferred to the ground by the coffin bone pressing directly down on the corium, the sole, and finally the ground.

This alternating pressure is what creates blood circulation in the sole corium. When the coffin bone presses down, blood is pushed out of the corium, and when the pressure is relieved, blood is drawn in. If the sole does not make ground contact under load, no blood circulation occurs in the corium.

If the sole is up in the air the horse’s entire weight is forced to find another path from the coffin bone to the ground.

If the hoof wall is the only part of the hoof with ground (shoe) contact

the weight will have to chose an odd way (red arrows) to reach the ground.

(Red arrows are pushing forces and blue arrows are pulling forces.)

The weight comes in the skeleton down to the coffin bone (big red arrow) that always stands on the sole corium and the sol.

If the sole doesn’t have ground contact the sole hangs from the hoof walls by the band of laminars.

This means that the band of laminars are suspending the whole horse,

and the sole becomes overloaded, bent, and stretched.

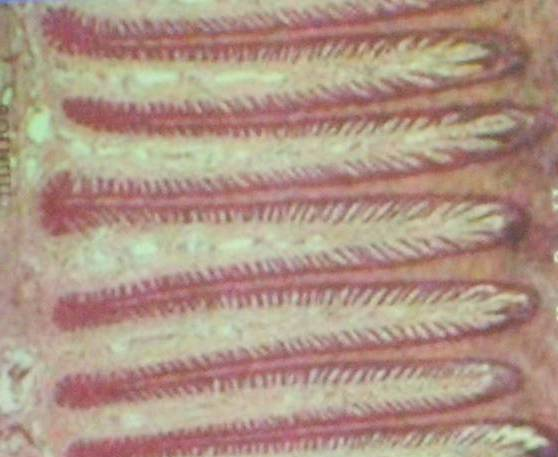

The reason the weight doesn’t go from the coffin bone through the lamellae, out to the hoof wall is because that would be even worse. Built into the hoof wall are primary lamellae (as thin as hair), and attached to them are secondary lamellae (even thinner than hair).

These secondary lamellae are connected to keratin fibers, which, in an unstructured network, traverse the blood filled corium and attach to the coffin bone. This means that there is not one single lamella that reaches all the way from the hoof wall to the coffin bone, and if the sole doesn’t get ground contact the horse’s entire weight ends up hanging either from the band of laminars or from the sensitive and blood-filled corium.

This is what an unstructured network can look like and I find it obvious that it can not bear weight (this is however not keratin fibers).

When the hoof suffers from laminitis, the connection between the primary and secondary lamellae is damaged. This means there is no longer any tissue capable of transferring any weight what so ever from the coffin bone to the hoof wall, and the slightest ground pressure will dislocate the hoof capsule under excrusiating pain. This pain experienced during laminitis comes from the remaining lamellae—still barely attached to the sensitive corium—being torn loose. As more and more lamellae lose their grip, the load on those remaining increases, and so does the pain.

If the toes were too long and thus being pushed upward away from the coffin bone by ground pressure, the hoof will be given the (incorrect) diagnosis of “coffin bone rotation.” The diagnosis of coffin bone rotation has nothing to do with the angle of the coffin bone relative to the ground—it only indicates that the toe wall and coffin bone are no longer parallel. I hope I have clarified that it is the now-loose toe wall that has been pushed away from the coffin bone, not the heavily loaded coffin bone locked inbetween the horse’s weight and the ground that has rotated in a way that defies the laws of physics.

Pain relief is achieved by trimming the hoof’s bottom in a way that makes it leave a foot print not more than 1cm= 3/8″ bigger than the coffin bone in width and toe length.

This may mean that the hoof must be reduced by trimming into the sole from the front and sides to remove what makes the hoof too large.

The coffin bone in the picture is the original one (no photo shop).

Use your imagination for how much you could trim.

The most I’ve ever shortened a Shetland pony’s hoof

(which did not appear to have a stretched band of laminar)

was to half its length.

However, it takes special training to reduce hoof size by trimming into the sole.

It’s often possible to trim away much more than traditional methods allow—but this is not a job for the untrained. But above all, the hoof wall and lamellae must be completely unloaded.

There are various signs in the hoof that, when considered together, can make even very radical trims completely safe and highly effective in relieving pain. A trim that relieves pain does so by removing the cause of the pain, while chemical pain relief only masks the cause.

A correctly performed trim for laminitis will let the horse voluntarily gallop in the paddock within 20 minutes after the trim. Riding can then begin as soon as the horse allows it since the cause of the pain has been trimmed away. However, it is important to remember that the hoof is not healthy just because it is pain-free. A hoof that has been deformed after laminitis cannot heal. All damage tissue must be replaced and therefore the hoof remains vulnerable to new deformation until the new hoof capsule has completely replaced the old one. During this regrowth, which replaces the damaged tissue with new, the hoof must be kept extremely well-trimmed for the horse to be excersised or ridden. The hoof wall must never be allowed to bear weight. This also means that under no circumstances should a laminitic hoof ever be shod.

- If the horse doesn’t run shortly after trimming, the hoof capsule is likely still bearing weight.

- If the pulse persists or returns after trimming, even though the hoof wall looks unloaded, the hoof is likely still too large.

A pulse in itself is not a problem; it just indicates that some body part requires more blood circulation, possibly to aid healing.