Laminitis is a common side effect of Founder.

The connection between founder and laminitis is not fully known, but what we do know is that founder resides in the body and laminitis resides in the hooves. The founder is not even classified as a disease; it is a number of issues that must be present at the same time, and other issues that can’t be present simultaneously. When a horse founders, something is released into the bloodstream, and when this something reaches the hooves, something happens to the connection between the coffin bone and the hoof wall that makes the hoof wall more or less loose. There are no treatments for either founder or laminitis.

No one can do anything to stop or cure the founder. There are two things that might be good to consider when it comes to founder-prevention. The first one is that an overload of glucose in the large intestine is considered a trigger for founder (but more about that comes in a separate lecture). The second one is intense exercise. 30 minutes of fast gallop 365 days per year is considered the best preparation for a founder-free life, but be very careful with taking breaks from this routine.

The only thing the veterinarians can offer a foundered horse is a painkiller and something anti-inflammatory, but there is neither pain nor inflammation associated with either founder or laminitis in itself. The pain affecting laminitic hooves comes from a side effect of laminitis, but that is something a good trim takes care of much better and more effectively.

No one can do anything to stop or cure the laminitis. A hoof deformed during laminitis can not be healed, only grow healthy, and when it has, it is just as strong as it was before it got laminitis.

The good news is, however, that no horse has ever died from either founder or laminitis.

It is the lack of successful rehabilitation of a side effect of a side effect of founder that far too often leads to the completely unnecessary death of laminitic horses. Let us change that here and now!

What happens in the hoof when it gets laminitis?

First, we must understand how the hoof is “put together” and what is attached to what. The skeleton bears the horse’s weight, and all the forces created by what we call weight ( a mass times gravity) point toward the center of the planet (i.e., straight down). The bones in the skeleton thus push directly downward against each other, causing all the weight to ultimately load the coffin bone in the hoof joint.

This means that the force created by the horse’s weight causes the coffin bone to press the corium directly down toward the sole, making the hoof sink into the ground until the ground pressure equals the pressure from the horse’s weight, and the hoof stops sinking.

When a barefoot hoof sinks into the ground, the pressure is distributed across the entire underside of the hoof, which reduces the load per unit area. Everything that leaves a footprint is being pressed up by ground pressure.

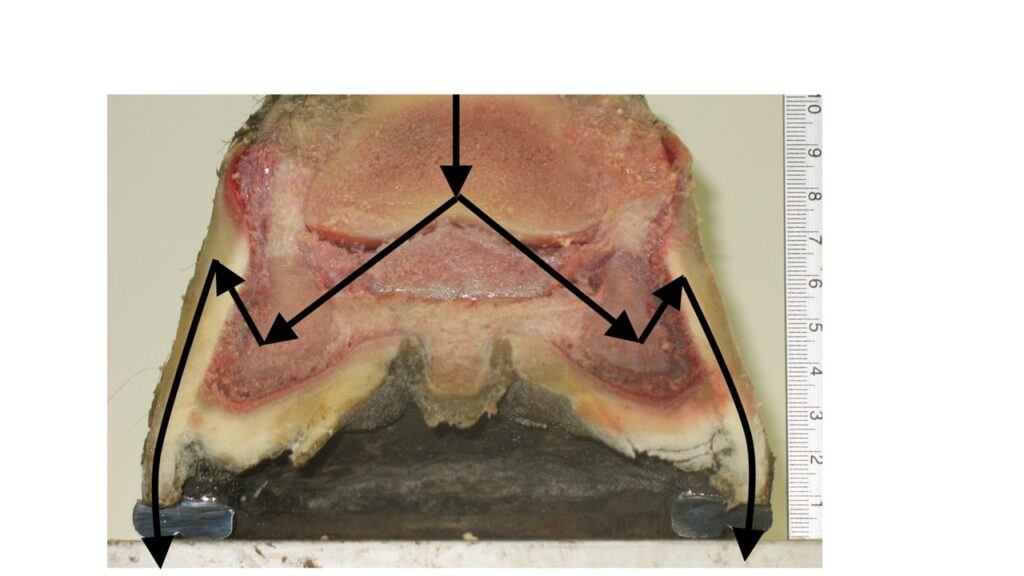

This picture was taken outside my neighbor’s farm, where humans affect everything about the hoof shapes and how they are loaded.

Everything that leaves a footprint is being pushed up by ground pressure (the arrowheads). The part of the hoof that is right under the coffin bone will be nicely affected by balanced forces from the horse’s weight and ground pressure, which will only result in compression of the sole corium (which creates blood circulation, but more about this in the lecture on coffin bones). If the hoof is larger than the coffin bone, the oversized part of the hoof will be pushed upward by the ground pressure (Red arrows) without any natural forces balancing it. This means that the outer part of the sole and the hoof wall will bend and stretch the sole since there is no weight pressing down.

The same applies if the hoof is shod and the hoof wall extends below the sole level, thus bearing weight. When the hoof wall is pushed upward relative to the coffin bone and the part of the sole beneath the coffin bone, unnatural forces will cause stretching of the hoof wall’s attachment (laminea) to the hoof capsule. A healthy hoof can withstand quite a lot of such forces compared to a hoof that has been affected by laminitis.

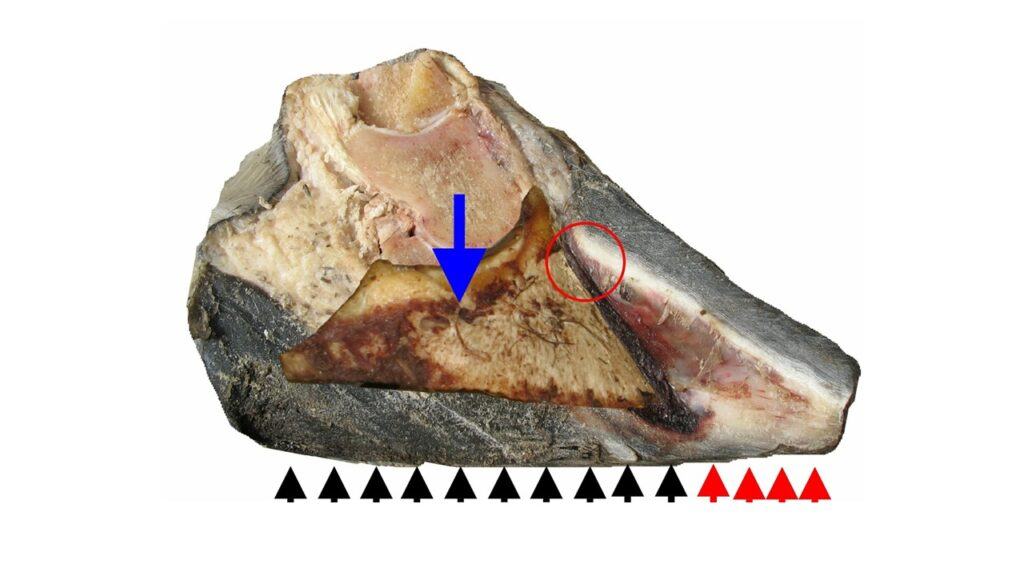

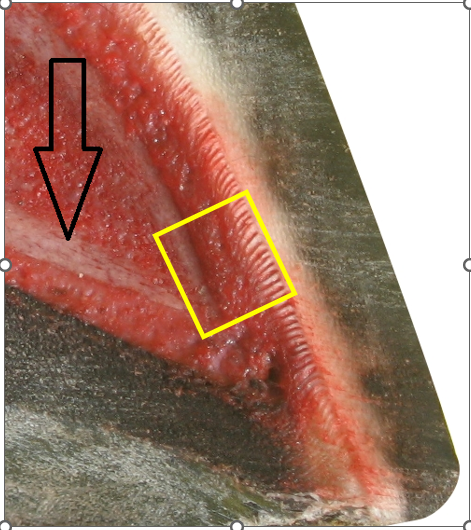

This very much enlarged picture shows a hoof wall with laminea that has been torn away from the coffin bone.

From the top: Hoof wall, laminae, what used to be corium, coffin bone.

In a laminitic hoof, the hoof wall will therefore be pushed upward relative to all other parts of the hoof/horse if it is forced to bear weight (be exposed to ground pressure). This almost without any resistance. This can be misunderstood as the coffin bone was sinking when it is the hoof wall that has been elevated compared to everything else. Lowering of the coffin bone should therefore be called something like “hoof wall elevation” to make the rehabilitation more logical. As long as the condition is called distal descent or lowering of the coffin bone, rehabilitation will focus on trying to push the coffin bone back up, but since the coffin bone is in direct contact with the short pastern bone and the rest of the skeleton, there is no space into which the coffin bone can be pushed up.

When it comes to the condition “coffin bone rotation,” the same principle applies: the horse’s entire weight, through the skeleton, presses the coffin bone straight down toward the corium, then to the sole, and then to the ground. There is neither a void in the hoof for the coffin bone to rotate into, nor is there a force pushing the front of the coffin downward—the short pastern bone applies pressure on the coffin bone’s rear, making such rotation physically impossible.

The blue arrow represents the horse’s weight, and the red area shows where the corium should be connected to the coffin bone.

Now it’s time to place your first bet: If the coffin bone were to “hang” from the red area, would not the back part of the bone then be more prone to “rotating” down since there is almost no area of connection between the coffin bone and the hoof wall behind the pressure point? That is, if there had not been a sole pressed to the ground below, of course.

– Everyone who answered: “The question is irrelevant since with ground pressure from below and the horse’s weight pressing down from above, the coffin bone can’t rotate in any direction”, is a winner. Congratulations.

As stated before, the horse’s weight is supposed to be transferred to the ground by the coffin bone pressing directly down on the corium, the sole, and finally the ground. But in what way would the weight go in a hoof where the hoof wall, due to metal shoes or protruding hoof walls, has been made weight-bearing?

Yes, I know that the tradition states that the coffin bone is hanging from the hoof wall by the laminae, but is that even possible?

Let us first look at what the tissue between the coffin bone and the hoof wall contains.

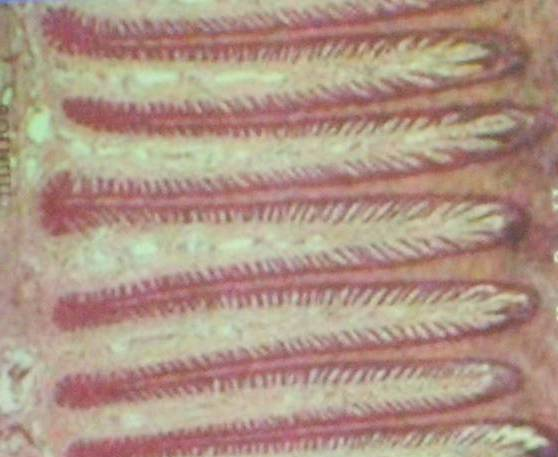

The primary lamina is approximately as thick as a hair in the horse’s tail and is a part of the hoof wall (to the left in the picture). They are “built in” to the hoof wall and will not let themselves be torn away from the bone. What comes from the right is the blood-filled corium. Between the lamina and the corium is also what is called the secondary lamina, with a thickness of 1/5 of the primary lamina. Please note that there is no coffin bone visible in the picture above.

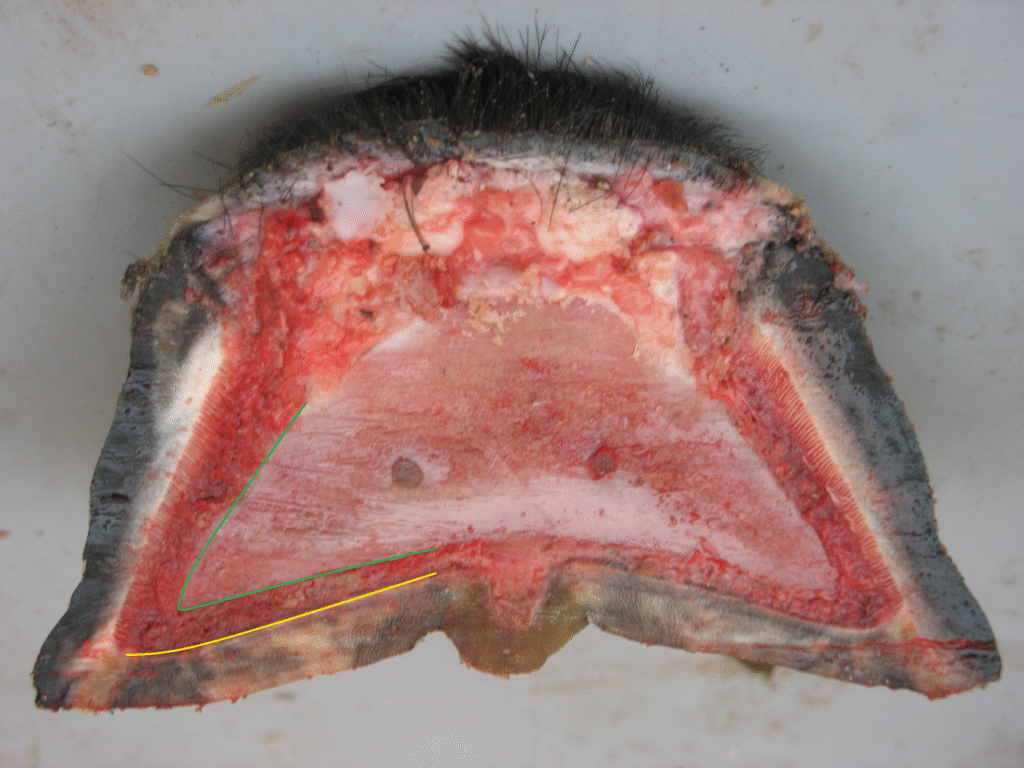

This picture shows a cross-section with the coffin bone in the middle. The corium is usually 3-10mm (1/10″ – 1/3″) thick and always blood-filled. This is where the hoof mechanism and blood-pumping take place. When the hoof capsule widens during the load face it fills with new blood, and when it is unloaded, the wall flexes in again, and blood is pressed back to the bone.

This picture shows a cross-section with the coffin bone in the middle. The corium is usually 3-10mm (1/10″ – 1/3″) thick and always blood-filled. This is where the hoof mechanism and blood-pumping take place. When the hoof capsule widens during the load face it fills with new blood, and when it is unloaded, the wall flexes in again, and blood is pressed back to the bone.

The corium is criss-crossed with an unstructured network of keratin fibers, but there is not a single lamina going all the way from the hoof wall to the coffin bone.

The above picture shows another unstructured network, but this one is not of keratin fibers.

If the sole doesn’t make ground contact when loaded, the horse’s entire weight is forced to find another path from the coffin bone to the ground.

The sad truth is that the whole horse will then stand on a” trampoline” (like the one kids are jumping on). ” If the hoof wall is the only part of the hoof with ground (shoe) contact

the weight will have to choose an odd way (red arrows) to reach the ground.

(Red arrows are pushing forces and blue arrows are pulling forces.)

The weight comes in the skeleton down to the coffin bone (big red arrow) that always stands on the sole corium and the sole.

If the sole doesn’t make ground contact, the sole hangs from the hoof walls by the band of laminars.

This means that the band of laminars is suspending the whole horse,

and the sole becomes overloaded, bent, and stretched.

The above picture shows a hoof where the sole made ground contact when the hoof was loaded. Remember the relation between the yellow line and the green line here, and look at the next picture.

This is a picture of a hoof where the high hoof walls made it impossible for the sole to make ground contact when loaded. Because the sole didn’t get any support from the ground, the coffin bone pressed down the sole from where it connects to the hoof wall. The hoof wall was pushed up by ground pressure, and the coffin bone was pressed down by the horse’s weight, which permanently deformed the sole

The reason the weight doesn’t go from the coffin bone through the lamellae, out to the hoof wall, as the tradition states, is because that would be even worse.

The above picture shows what the tradition states about how the horse’s weight reaches the ground. During this class, I will gradually stack up a pile of reasons and evidence for that the tradition is completely wrong, and that is the main reason why so many horses lose their life due to hoof complications.

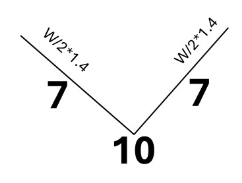

Let me give you one more here. If you want to lift something with a rope, the rope must go straight up from the object you want to lift, or you will get problems. If you are using one rope and it doesn’t go straight up, you will drag the object to the side instead of lifting it. If you use two ropes, each one at a 45-degree angle, the force in each rope will be approximately 1.4 times higher compared to if the ropes had gone straight up.

If you don’t believe me, ask Chat GPT “What will happen to the forces if I want to lift an object using two ropes going 45 degrees to the side instead of straight up?”

So what does this have to do with hooves?

Okay, if the laminae were intended to lift the coffin bone (the whole horse), they would have gone straight up from the bone, but do they?

To me, it looks like they are much more angled perpendicular to the hoof wall (straight out from) than vertical (like the black arrow). This means that their job is to absorb forces going 90 degrees to the hoof wall, like keeping the hoof capsule in place when the horse is taking a sharp turn, not lifting the coffin bone.

Pain relief connected to laminitis is achieved when ground pressure no longer breaks the hoof wall away from the coffin bone. This means trimming the hoof to leave as small hoof prints as possible. Small hooves = less leverage for the ground pressure = less pain.

This means that the hoof below must be reduced by trimming far into the sole from the front and sides to remove the leverage that a too-big hoof capsule brings.

The coffin bone in the picture is the original one (no Photoshop).

Use your imagination for how much you could trim.

The most I’ve ever shortened a Shetland pony’s hoof

(which did not appear to have a stretched band of laminar)

was to be half its length.

However, it takes special training to reduce hoof size by trimming into the sole.

It’s often possible to trim away much more than traditional methods allow—but this is not a job for the untrained. I have done hundreds of extreme toe shortenings, and my students have done just as many, all without a single drop of blood. Drawing blood is only for the ignorant

It’s often possible to trim away much more than traditional methods allow—but this is not a job for the untrained. I have done hundreds of extreme toe shortenings, and my students have done just as many, all without a single drop of blood. Drawing blood is only for the ignorant.

There are various signs in the hoof that, when considered together, can make even very radical trims completely safe and highly effective in relieving pain. A trim that relieves pain does so by removing the cause of the pain, while chemical pain relief only masks the cause.

A correctly performed trim for laminitis will let the horse voluntarily gallop in the paddock within 20 minutes after the trim. Riding can then begin as soon as the horse allows it, since the cause of the pain has been trimmed away, there is no risk involved anymore. However, it is important to remember that the hoof is not healthy just because it is pain-free. A hoof that has been deformed after laminitis cannot heal. All damaged tissue must be replaced, and therefore, the hoof remains vulnerable to new deformation until the new hoof capsule has completely replaced the old one. During this regrowth, which replaces the damaged tissue with new, the hoof must be kept extremely well-trimmed for the horse to be exercised or ridden. The hoof wall must never be allowed to bear weight. This also means that under no circumstances should a laminitic hoof ever be shod.

- If the horse doesn’t gallop shortly after being trimmed, the hoof capsule is likely still bearing weight.

- If the pulse persists or returns after trimming, even though the hoof wall looks unloaded, the hoof is likely still too large.